From Hide-and-Seek to Homo Digitalis: The Changing Landscape of Play

If you’re over 30, chances are your childhood was filled with outdoor games like hide-and-seek, hopscotch, or cricket—those carefree afternoons that seemed to stretch forever. Perhaps you also spent some time glued to a TV screen, playing classics like Mario, Contra, Tetris, or Snake. Remember the satisfying click of the game controller buttons—and the thumb cramps that came with it? Fun fact: that ache even has a name—Gamer’s Thumb (or De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis). Who knew, right?

Back then, video games were a simple escape, a quick dose of joy before heading back to schoolwork or chores. We even embraced the wisdom of that old saying, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” Play was a balance, and life felt richer because of it.

But times have changed. Gaming is no longer a fleeting pastime; it’s become immersive, serious, and—for some—a way of life. Think about the modern juggernauts: PUBG, Fortnite, or Call of Duty. These games aren’t just for fun anymore; they’re built for endless engagement. Combined with societal shifts—like the rise of social media and more isolated family structures—this constant connectivity has paved the way for addiction-like tendencies.

The Internet’s global reach has fundamentally reshaped how we live, so much so that some sociologists and psychologists now call the digital-native generation Homo digitalis or Homo technologicus. Gaming Disorder, a byproduct of this transformation, is no longer an emerging concern; it’s a recognized global phenomenon that demands attention.

Internet Gaming Disorder in DSM-5-TR

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), serves as the gold standard for diagnosing mental health conditions. Within its pages, the phenomenon of gaming addiction is described under the term Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD). While not yet classified as a formal diagnosis, IGD is listed in the section recommending conditions for further research, alongside others like caffeine use disorder.

This inclusion highlights the growing concern surrounding excessive gaming, as it parallels patterns seen in other addictive behaviors. The DSM-5-TR primarily categorizes addictive disorders into two groups: substance-related (e.g., alcohol, opioids, and stimulants) and behavioral. Of these, Gambling Disorder remains the only officially recognized behavioral addiction, setting a precedent for IGD’s potential classification in the future.

Only non-gambling Internet games are included in IGD. Use of the Internet for required activities in a business or profession is not included; nor is the disorder intended to include other recreational or social Internet use. Similarly, sexual Internet sites are excluded.

Proposed Criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder in DSM-5-TR

Persistent and recurrent use of the Internet to engage in games, often with other players, leading to clinically significant impairment or distress as indicated by five (or more) of the following in a 12-month period:

- Preoccupation with Internet games. (The individual thinks about previous gaming activity or anticipates playing the next game; Internet gaming becomes the dominant activity in daily life.)

- Withdrawal symptoms when Internet gaming is taken away. (These symptoms are typically described as irritability, anxiety, or sadness, but there are no physical signs of pharmacological withdrawal.)

- Tolerance—the need to spend increasing amounts of time engaged in Internet games.

- Unsuccessful attempts to control the participation in Internet games.

- Loss of interests in previous hobbies and entertainment as a result of, and with the exception of, Internet games.

- Continued excessive use of Internet games despite knowledge of psychosocial problems.

- Has deceived family members, therapists, or others regarding the amount of Internet gaming.

- Use of Internet games to escape or relieve a negative mood (e.g., feelings of helplessness, guilt, anxiety).

- Has jeopardized or lost a significant relationship, job, or educational or career opportunity because of participation in Internet games.

Internet gaming disorder can be mild, moderate, or severe depending on the degree of disruption of normal activities. Individuals with less severe Internet gaming disorder may exhibit fewer symptoms and less disruption of their lives. Those with severe Internet gaming disorder will have more hours spent on the computer and more severe loss of relationships or career or school opportunities.

Gaming disorder in ICD-11

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), is a globally recognized standard for recording and reporting health and health-related conditions. The ICD plays a pivotal role in ensuring interoperability and comparability of digital health data, encompassing diseases, disorders, health conditions, and more. The inclusion of any specific condition in the ICD requires sufficient evidence of its existence and utility across diverse global healthcare contexts.

In the 11th Revision of the ICD (ICD-11), Gaming Disorder is recognized under the code 6C51. It is defined as a pattern of gaming behavior, whether digital or video-based, that exhibits: impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that it displaces other interests and daily responsibilities, and continuation or escalation of gaming despite negative consequences.

For Gaming Disorder to be diagnosed, the pattern of behavior must cause significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other critical areas of functioning. Furthermore, this behavior typically needs to persist for at least 12 months to warrant a diagnosis.

Diagnostic Requirements for Gaming disorder in ICD-11

Essential (Required) Features:

A persistent pattern of gaming behaviour (‘digital gaming’ or ‘video-gaming’), which may be predominantly online (i.e., over the internet or similar electronic networks) or offline, manifested by all of the following:

- Impaired control over gaming behaviour (e.g., onset, frequency, intensity, duration, termination, context);

- Increasing priority given to gaming behaviour to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other life interests and daily activities; and

- Continuation or escalation of gaming behaviour despite negative consequences (e.g., family conflict due to gaming behaviour, poor scholastic performance, negative impact on health).

- The pattern of gaming behaviour may be continuous or episodic and recurrent but is manifested over an extended period of time (e.g., 12 months).

- The gaming behaviour is not better accounted for by another mental disorder (e.g., Manic Episode) and is not due to the effects of a substance or medication.

- The pattern of gaming behaviour results in significant distress or impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Specifiers for online or offline behaviour:

- 6C51.0 Gaming Disorder, predominantly online: This refers to Gaming Disorder that predominantly involves gaming behaviour that is conducted over the internet or similar electronic networks (i.e., online).

- 6C51.1 Gaming Disorder, predominantly offline: This refers to Gaming Disorder that predominantly involves gaming behaviour that is not conduced over the internet or similar electronic networks (i.e., offline).

- 6C51.Z Gaming Disorder, unspecified

Additional Clinical Features:

- If symptoms and consequences of gaming behaviour are severe (e.g., gaming behaviours persist for days at a time without respite or have major effects on functioning or health) and all other diagnostic requirements are met, it may be appropriate to assign a diagnosis of Gaming Disorder following a period that is briefer than 12 months (e.g., 6 months).

- Individuals with Gaming Disorder may make numerous unsuccessful efforts to control or significantly reduce gaming behaviour, whether self-initiated or imposed by others.

- Individuals with Gaming Disorder may increase the duration or frequency of gaming behaviour over time or experience a need to engage in games of increasing levels of complexity or requiring increasing skills or strategy in an effort to maintain or exceed previous levels of excitement or to avoid boredom.

- Individuals with Gaming Disorder often experience urges or cravings to engage in gaming during other activities.

- Upon cessation or reduction of gaming behaviour, often imposed by others, individuals with Gaming Disorder may experience dysphoria and exhibit adversarial behaviour or verbal or physical aggression.

- Individuals with Gaming Disorder may exhibit substantial disruptions in diet, sleep, exercise and other health-related behaviours that can result in negative physical and mental health outcomes, particularly if there are very extended periods of gaming.

- High-intensity gaming behaviour may occur as a part of online computer games that involve coordination among multiple users to accomplish complex tasks. In these cases, peer group dynamics may contribute to the maintenance of intensive gaming behaviours. Regardless of the social contributions to the behaviour, the diagnosis of Gaming Disorder may still be applied if all diagnostic requirements are met.

- Gaming Disorder commonly co-occurs with Disorders Due to Substance Use, Mood Disorders, Anxiety or Fear-Related Disorders, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and Sleep-Wake Disorders.

Psychological Tests for Gaming Disorder

As a therapist or psychologist, staying equipped with effective tools is essential for diagnosing and addressing new and pervasive mental health challenges like Gaming Disorder. With the rise of digital and internet-related issues, having accurate, research-backed assessments at your disposal can make all the difference in identifying and understanding problematic behaviors.

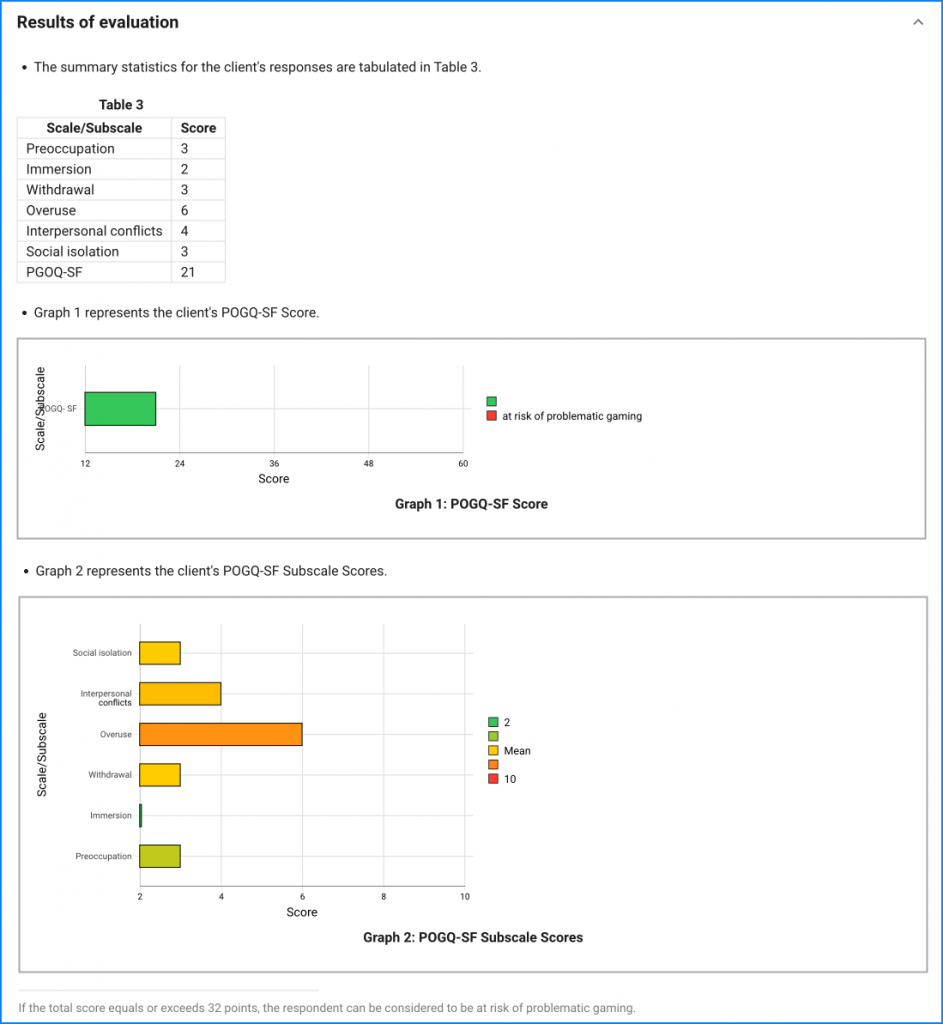

Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire Short-Form

The Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire Short-Form (POGQ-SF) is a concise yet robust tool designed to assess problematic gaming behaviors. This 12-item questionnaire evaluates issues across six key dimensions:

- Preoccupation refers to obsessive thinking and daydreaming on the online game.

- Overuse contains items concerning the excessive use of online games.

- Immersion indicates dealing excessively with online games, immersion in gaming, and losing track of time.

- Social Isolation indicates damage to social relationships, and the preference of gaming over social activities.

- Interpersonal Conflicts refers to the comments of the player’s social environment on overuse of online games and the related conflicts.

- Withdrawal concerns the appearance of withdrawal symptoms in cases when players experienced difficulties in gaming as much as they wanted.

PsyPack automatically generates detailed results for the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire Short-Form (POGQ-SF), with clear visualizations across its six subscales, as shown in the screenshot below. This allows practitioners to quickly interpret and act on the findings for effective intervention.

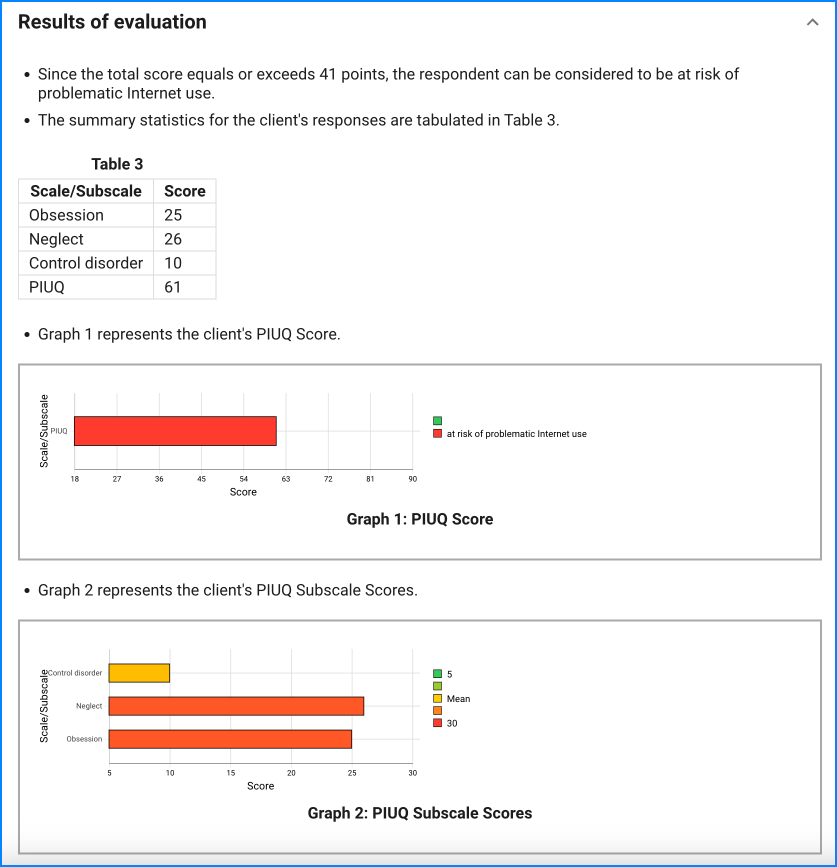

Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire – Adult and Youth Version

The Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ-18) is a comprehensive tool for evaluating challenges related to internet use. Comprising 18 items, it assesses three key subscales:

- Obsession: The substance of these items was, on the one hand, mental engagement with the Internet—that is, daydreaming, fantasizing a lot about the Internet, waiting for the next time to get online—and, on the other hand, anxiety, worry, and depression caused by lack of Internet use.

- Neglect: The substance of these items was neglect of everyday activities and essential needs. Items about the decreasing importance of household chores, work, studies, eating, partner relations, and other activities and the neglect of these activities due to an increased amount of Internet use were included.

- Control Disorder: These items referred to difficulties in controlling Internet use. They expressed the fact that the person used the Internet more often and/or for a longer time than had previously been planned and that, despite his or her plans, he or she was not able to decrease the amount of Internet use. Items also referred to perceiving Internet use as a problem.

The Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire (PIUQ) is available on PsyPack in both Adult and Youth Versions. It simplifies scoring across the three subscales—obsession, neglect, and control disorder—by automatically generating detailed results, as shown in the screenshot below, providing practitioners with clear and actionable insights to address problematic internet behaviors effectively.

If you’re a psychologist, therapist, psychiatrist, social worker, or behavioral health professional, PsyPack is here to support your journey in providing better care. With tools designed to make assessments simpler and more insightful, you can create a free account and explore how PsyPack seamlessly integrates into your practice. Take the first step toward enhancing your client work—one meaningful assessment at a time.

Recent Stories Highlighting Gaming Concerns

The gaming industry, driven by the need to create engaging experiences that trigger repeated dopamine hits, faces increasing scrutiny as concerns over addiction grow. With gaming companies under legal and regulatory pressure, governments are experimenting with measures to address the issue. While the media may downplay these challenges, the issue is very real. We’ve compiled a few key stories to highlight the ongoing concerns and raise awareness about gaming’s impact.

- The infamous Blue Whale Challenge, which led to dangerous and self-harming behavior among teens globally. Read BBC’s story here.

- China imposing strict gaming limits on minors, restricting online gaming to just three hours a week. Read NIKOs story here.

- South Korea replaces its restrictive “Cinderella Law” with a more flexible “Choice System,” allowing parents to set gaming limits for children. Read TechSpot’s story here.

- Japan’s 2020 Kagawa Prefecture introduced limits on children’s gaming time, capping it at one hour on school nights and 90 minutes on weekends, aiming to tackle video game addiction concerns. Read Hustle’s story here.

- Game publishers are facing increasing scrutiny over gaming addiction and are responding by introducing warnings and parental controls to limit excessive usage, with Epic Games’ Fortnite leading the charge by offering screen time controls and spending limits. Read CitizenSide’s story here.

- The rise of loot boxes in games like FIFA and Fortnite has raised concerns about their similarity to gambling, with some countries pushing for regulations due to potential addictive behaviors. Read Gambling News’s story here.

- Concerns have been raised about Grand Theft Auto V’s realistic violence, with critics arguing that it may desensitize players to aggression and real-world violence, while supporters maintain that it is merely a fictional and artistic medium for entertainment. Read Medical Daily’s story here.

As the world evolves, the overuse of our once-innocent beloved games is becoming a growing health concern for the next generation. As behavioral health practitioners, it’s vital that we stay updated with the fast-changing landscape of psychology, equip ourselves with the right psychological tools, and spread awareness through our work to help those affected by gaming-related issues.

Until next time, I’m off to responsibly play my favorite game of Sudoku. Let’s remember, moderation is key!